I am sure we all know that the Fourier Transform is a mathematical operation that transforms a time-domain signal into its frequency-domain representation. This transformation is crucial in various fields, including signal processing, communications, and audio analysis.

The plain continuous Fourier Transform (CFT) of a time-domain signal is defined by the integral:

Where:

- is the complex exponential function that represents the basis functions for the transformation.

- is the frequency variable in Hertz (Hz).

- is the imaginary unit, satisfying .

- is the time variable.

This is the case for an infinite continuous signal. In practice, we often deal with discrete signals sampled at specific intervals, this can still be done in the continuous domain, but more commonly we use the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) for sampled signals.

Intuition

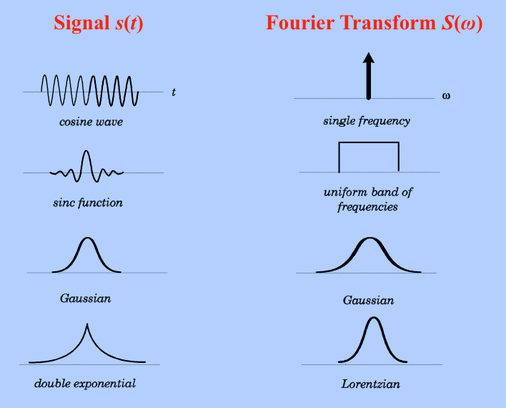

Probably one of the most elegant pieces of mathematics, especially how we use exponential Phasors to represent sinusoids. The Fourier Transform essentially decomposes a signal into its constituent frequencies, allowing us to analyze the frequency content of the signal.

We will decompose the equation into its parts. Overall, this term can be thought of as the “frequency generator”, the only difference is that the generated frequency is of a different form factor that splits into real and imaginary parts.

The Exponential Term

We know that has the simple effect of rotating a point around the origin in the complex plane by an angle . In this case we use , but the concept is the same.

Why the ?

This is just a scaler to make it such that one “unit” of rotation is equal to one full rotation in radians, which is . We expect a rotator of time 1 and frequency 1 to rotate radians.

The Parameter

This is our main “knob” in the Fourier Transform. This is the frequency we are analyzing the signal for. The Fourier Transform will compute how much of this frequency is present in the signal. Now that everything else is normalized to time, this frequency is in Hertz (cycles per second).

Why the Negative Sign?

By default the Phasor rotates in the counter clockwise direction. The reason we make it negative and thus clockwise is because of the way we define positive frequencies in signals. Positive frequencies correspond to counter-clockwise rotation in the complex plane, so to analyze a positive frequency component in the signal, we need to rotate clockwise to “match” that frequency.

The Signal Multiplication

Because of the nature of the exponential term, the effect of multiplying at a unit time has the effect of seeing how well that frequency “matches” the signal at that time. If the signal has a strong component at that frequency, the multiplication will yield a larger value, while if the signal has little to no component at that frequency, the multiplication will yield a smaller value.

The signal is one dimensional, while the exponential is two dimensional (real and imaginary). The multiplication will thus project the signal onto the complex plane defined by the exponential term.

However because this is an integral, this is being done for each unit in time, from negative infinity to positive infinity. This means that we are effectively summing up all the contributions of the signal at that frequency over all time, and finding the “area under the curve” of that frequency component in the signal.

The Integral

You might recognize the structure of the Fourier transform as mirrorign that of a Convolution. This is because the Fourier Transform can be thought of as a special case of convolution, where we are convolving the signal with a complex exponential function. By integrating over all time, for each frequency, we are testing different frequencies against the signal to see how much of that frequency is present in the signal.

Extra: What role does magnitude and phase play?

These issues come up with techniques like IQ Sampling where we are dealing with complex signals. The Fourier Transform will yield a complex result for each frequency, which can be interpreted in terms of magnitude and phase.

But in plain english, the magnitude tells us how much of that frequency is present in the signal, while the phase tells us about the timing of that frequency component relative to the start of the signal. The phase can be important in applications/radar like communications, where the timing of signals is crucial.

Extentions

While incredibly useful, it is rarely used in this exact form in practice. It is not only a computationally expensive operation, but only works for actual mathematical continuous signals.

For snippets in time(often with limited samples resolution), we use the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) or its computationally efficient counterpart, the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). These transforms operate on discrete signals and provide a frequency-domain representation similar to the CFT.

But you may notice from things like Waterfall spectograms on SDR/Radio stations, is that we seems to have a time-varying frequency representation. This is achieved through the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), which involves segmenting the signal into smaller time windows and applying the Fourier Transform to each segment. This allows us to analyze how the frequency content of the signal changes over time.