There are two main approaches to evolutionary robotics: the “Italian” approach and the “English” approach. These terms were coined by Stefano Nolfi and Dario Floreano in their book Evolutionary Robotics to describe different philosophies in the field.

Italian Approach

Where we do evolutionary robotidcs on a physical robot directly. Emphasis on importance of real-world interactions and embodiment. The Italian approach focuses on evolving controllers and morphologies directly on physical robots, allowing them to adapt to the complexities and uncertainties of the real world.

The Khepera robot

Developed at EPFL Lausanne, Switzerland, by Francesco Mondada

- Diameter: 55 mm

- Could perform experiments on a table, rather than in a large arena.

How Italian Approach Learns

For the example of simple navigation through a maze, the Italian Approach has two simple goals:

- Traverse the maze as quickly as possible.

- Do not hit walls.

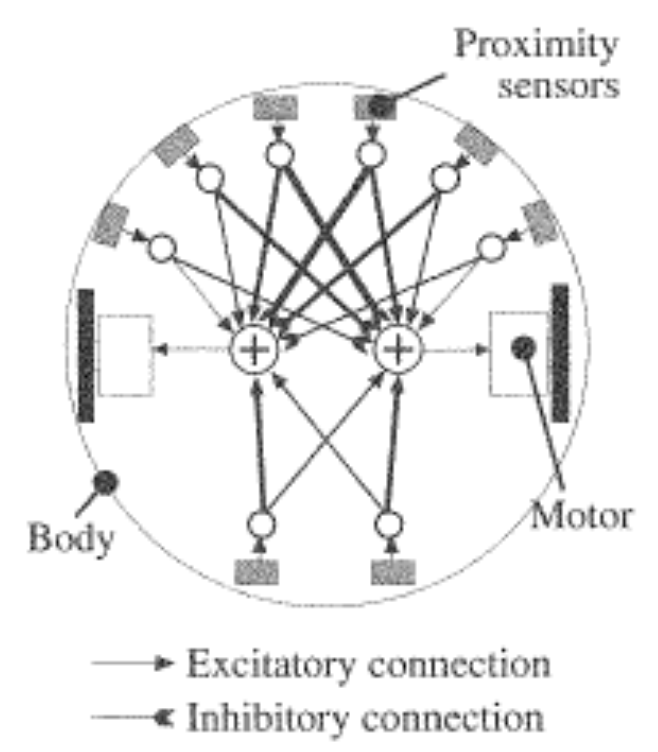

Robot is given the NN architecture shown.

Robot’s wheels can:

- rotate backwards quickly (-0.5)

- stay still (0.0)

- rotate forward quickly (0.5)

- or anything in this range [-0.5,0.5]

Robot’s eight proximity sensors return:

- 0 if obstacle is 5cm or further (or absent)

- 1 if proximity sensor is touching object.

- Or anything in this range [0,1]

The algorithm at play here is a simple (1+1) evolutionary strategy, where we include penalties and rewards based on the robot’s performance in the maze.

Khepara got penalized for driving into walls, but also for taking too long to complete the maze. It was rewarded for moving forward quickly.

A rough algorihtm would look something like:

Where:

- is the fitness score

- is the forward velocity of the robot

- is the sum of all infrared sensor readings (proximity sensors)

- is the time taken to complete the maze.

English Approach

The English approach evolves controllers in simulation first, then transfers to physical hardware. Core idea: leverage computational speed and control of simulated environments to iterate rapidly, then deploy successful solutions to real robots.

Physics engines like ODE handle the heavy lifting—bodies, joints, collision detection, gravity. Evolution happens in this simulated space where fitness evaluations are cheap and fast compared to physical trials.

The Gantry robot

University of Sussex, UK, by Inman Harvey et al.

Gantry robot was mounted on an overhead framework with three degrees of freedom, essentially a robotic arm that could position a wheeled robot anywhere in the arena from above. This hybrid approach let them validate simulation-evolved controllers in physical space while maintaining precise control over position and orientation.

The gantry system acts as a middle ground: not fully autonomous like the Italian approach, but testing real sensors and actuators in the physical world rather than staying purely in simulation.

English Approach Learning Method

Evolution runs entirely in simulation using a physics engine. Same general structure as the Italian approach—neural network controllers, evolutionary algorithms—but the robot only exists as simulated bodies and joints.

- Define robot morphology in simulation (bodies, joints, sensors)

- Initialize random population of neural network controllers

- Evaluate fitness in simulated environment (thousands of trials per generation)

- Select, mutate, recombine—standard evolutionary loop

- After convergence, transfer best controller to physical robot

The Reality Gap Problem:

Simulation is never perfect. Physics engines approximate friction, collision dynamics, sensor noise. Controllers that work flawlessly in simulation often fail on physical hardware due to:

- Unmodeled sensor noise and latency

- Simplified friction and contact dynamics

- Missing environmental complexity

- Actuator response differences

The gantry robot at Sussex partially addressed this by testing evolved controllers in a semi-physical setup. The overhead framework controlled position while real sensors and motors operated, revealing discrepancies between simulation and reality before full autonomy.