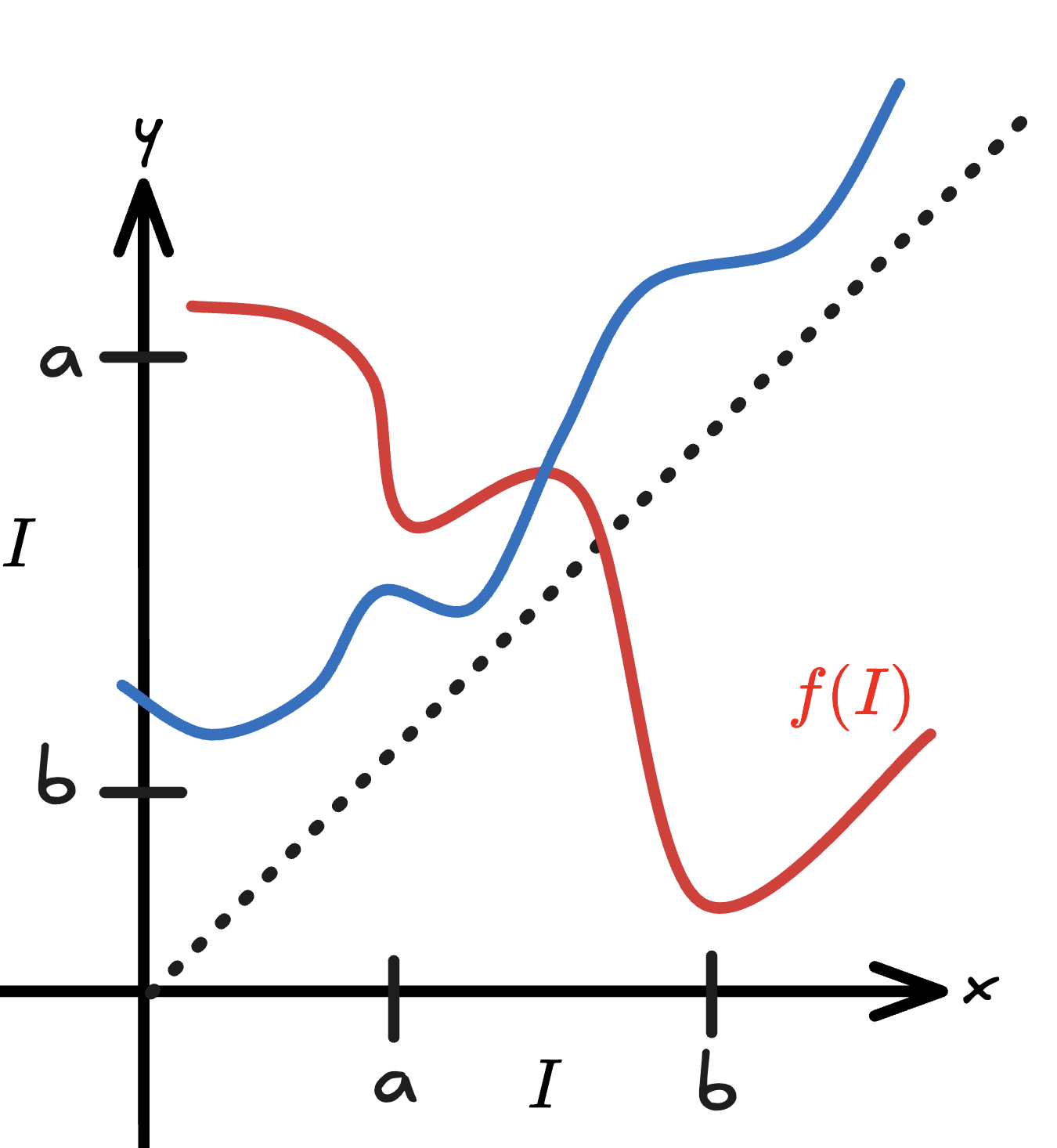

If we want to show that has chaotic orbits, we will do it by comparing with ( our Tent Map ).

For each point in the Tent Map domain , there is a companion point in the domain of that imitates its dynamics.

We say the maps and are conjugate if they are related by a continuous one to one change of coordinates.

Example

or

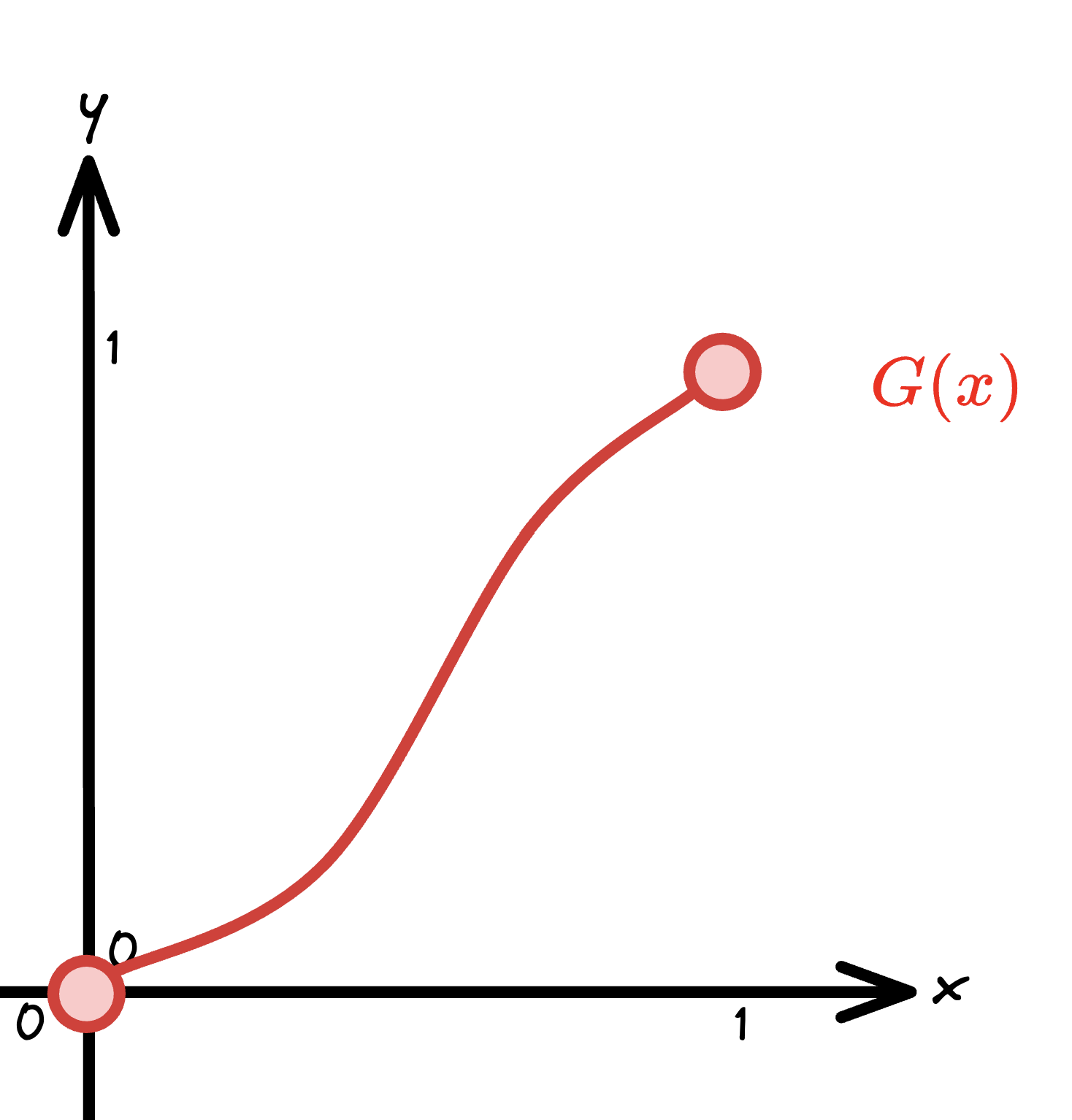

The maps and are conjugate by:

and:

For :

Idea

Two ways of getting from domain of to range of after iterations:

Evaluate directly — expensive, analytically intractable for large

Use conjugacy: since , induction gives , so:

Map into T’s domain via , iterate the simpler tent map times, then map back. Orbit structure of is exactly that of , just seen through the lens .

Suppose for a Fixed Point and then:

So stability of Fixed Point of and stability of Fixed Point , for are the same

Transition Graphs

Theorem (Covering implies fixed point)

The blue line in the figure is the counterexample — a function where , so IVT doesn’t force a fixed point.

In topology, the general version is Brouwers Fixed Point Theorem.

Setup

A partition of the interval is a collection of subintervals that are pairwise disjoint (except at endpoints) whose union is the whole interval.

For both and , the natural partition is :

Definition: Draw an arrow in the transition graph if and only if — ” of covers “.

The covering condition matters because: if , then by the Intermediate Value Theorem there exists a point in that maps into . Covering arrows are existence guarantees for orbits.

Computing the Graph for

The Tent Map with :

- and

- and

All four arrows exist. The Tent Map transition graph is completely connected.

By conjugacy, has the same graph — also maps both and surjectively onto .

A path of length in the graph is a sequence where each arrow is a valid transition. This corresponds to an admissible itinerary; there genuinely exists a point whose orbit visits in order.

Consequence of complete connectivity: Every infinite sequence over is admissible. That’s an uncountable family of distinct symbolic trajectories, each encoding a genuinely different orbit.

Periodic orbits from cycles: A cycle of length in the graph (e.g. returning to ) guarantees a period- orbit exists in that sequence of intervals. Since all arrows exist, cycles of every length exist → infinitely many periodic orbits.